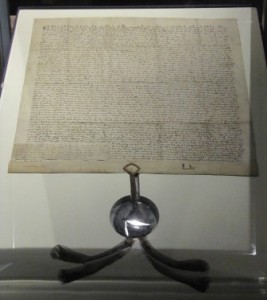

Magna Carta: 798 years after Runneymede…

Ideas have consequences and the ideas about justice and liberty under law promulgated in Magna Carta have had some of the most profound consequences in mankind’s history.

Originally intended by the English barons as a check upon the authority, privileges and prerogatives of King John, Magna Carta came to represent the essential foundation of English liberties, of the supremacy of the rule of law, of defending the rights of the individual from the exercise of arbitrary political power. And, as the basis of English jurisprudence, Magna Carta was carried across the Atlantic to the English colonies established in the New World; indeed, America’s Founding Fathers saw Magna Carta as one of the most important documents underpinning their Revolution, even as Magna Carta and its provisions were being eclipsed by the rise of Parliamentary Sovereignty in England.

Today, just three of the clauses appear to be extant: (1) freedom for the Church of England; (9) that relating to restoring the old liberties and customs of the Corporation of the City of London, as well as extending such to other cities, ports and boroughs and so on; and, finally, (29) the importance of procedural justice, whereby no punishments, no imprisonment nor restriction of liberties nor even the seizure of assets may be done “but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the Land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either Justice or Right.”

Nearly 800 years after Magna Carta was signed at Runneymede, despite almost all of its clauses being specifically repealed by legislation, the original spirit of many of its various clauses still resonate within and animate our social institutions, inform our customs and expectations. Yet one of Magna Carta’s most important provisions, Clause 29 relating to the administration of justice, has faced centuries of threat precisely because of the restraints it places upon the exercise of power. Only last month (May 2013), the Daily Mail reported how “Britain’s top police chief backs law to keep courts secret – even when journalists know the suspects“.

Nearly 800 years after Magna Carta was signed at Runneymede, despite almost all of its clauses being specifically repealed by legislation, the original spirit of many of its various clauses still resonate within and animate our social institutions, inform our customs and expectations. Yet one of Magna Carta’s most important provisions, Clause 29 relating to the administration of justice, has faced centuries of threat precisely because of the restraints it places upon the exercise of power. Only last month (May 2013), the Daily Mail reported how “Britain’s top police chief backs law to keep courts secret – even when journalists know the suspects“.

That Britain’s top cop, Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe (Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police Force in London), should publicly advocate legal changes not merely to allow but to require the identity of those arrested to be kept secret is extremely worrying. Even more disturbing is the fact that Hogan-Howe’s view is apparently entirely endorsed by the Home Secretary, Theresa May MP, whom the Daily Mail goes on to quote as saying: “I believe that there should be a right to anonymity at arrest, but I know there will be circumstances in which the public interest means that an arrested suspect should be named.”

Some have charged that the Leveson Report – with all of its many proposed abridgments to free speech – made a similar recommendation; whilst it does not, it is interesting that the Hacked Off campaign’s Hugh Tomlinson QC, in a short article “Leveson, “secret arrests” and the rights of suspects: a question of balance”, should approvingly cite Lord Leveson supporting just such an approach, i.e. that the police should not reveal the identity of those arrested:

I think that the current guidance in this area needs to be strengthened. For example, I think that it should be made abundantly clear that save in exceptional and clearly identified circumstances (for example, where there may be an immediate risk to the public), the names or identifying details of those who are arrested or suspected of a crime should not be released to the press nor the public. Leveson Report, Vol 2, Part G, chapter 4, par 2.39, p.791

One voice raised against such pernicious developments was that of Lord MacDonald, the former Director of Public Prosecutions, whom the Daily Mail article reported as declaring that:

There should be a presumption police will reveal names of arrested people… It’s important the public are told who police are locking up.

Why? Because whilst such apparent secrecy does not, in of itself, constitute an absolute violation of an individual’s right to a fair trial, it does rather undermine the principle of habeas corpus: how can a friend or family member act on the arrested person’s behalf by seeking a writ of habeas corpus from a court, to force the authorities to take notice of the fact that someone is being held without recourse to justice, if their identity (and, thus, the fact of their custody) is effectively being kept secret by the police?

Why? Because whilst such apparent secrecy does not, in of itself, constitute an absolute violation of an individual’s right to a fair trial, it does rather undermine the principle of habeas corpus: how can a friend or family member act on the arrested person’s behalf by seeking a writ of habeas corpus from a court, to force the authorities to take notice of the fact that someone is being held without recourse to justice, if their identity (and, thus, the fact of their custody) is effectively being kept secret by the police?

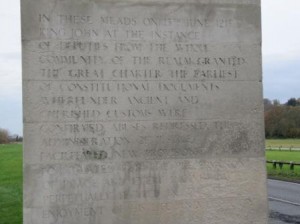

As Britain approaches the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta, of the signing of the Great Charter of the Liberties of England in that field by the River Thames at Runneymede on 15th June 1215, one of the most fundamental aspects of our ancient liberties is now under increased threat from the very people and agencies that we, the people, entrust to protect it: the right to justice. Nor is this threat to liberty anything new; in his thought-provoking 2005 Magna Carta address, Sir Bob Worcester discussed how since Magna Carta was signed, the principles of liberty and justice it expounded have had to contend with continuous attack from every side. (The Magna Carta at 800: Foundation of Liberty project is worth checking out; follow it #MagnaCarta800th for more updates.) And just as in 1215 and in all the years that followed, Magna Carta may also provide that focus that we need to defend our rights and liberties from those who would threaten them in the name of “security” or simply to control and enslave us.

As Britain approaches the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta, of the signing of the Great Charter of the Liberties of England in that field by the River Thames at Runneymede on 15th June 1215, one of the most fundamental aspects of our ancient liberties is now under increased threat from the very people and agencies that we, the people, entrust to protect it: the right to justice. Nor is this threat to liberty anything new; in his thought-provoking 2005 Magna Carta address, Sir Bob Worcester discussed how since Magna Carta was signed, the principles of liberty and justice it expounded have had to contend with continuous attack from every side. (The Magna Carta at 800: Foundation of Liberty project is worth checking out; follow it #MagnaCarta800th for more updates.) And just as in 1215 and in all the years that followed, Magna Carta may also provide that focus that we need to defend our rights and liberties from those who would threaten them in the name of “security” or simply to control and enslave us.